What Makes Up an Ultrasonic Cleaning Solution

Browse Volume:46 Classify:Support

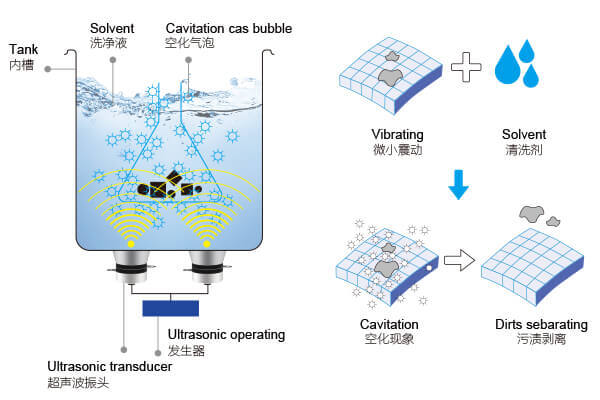

Anyone who has ever watched an ultrasonic cleaner in action knows how deceptively simple the process looks. You place the item into the tank, add a liquid, press a button, and wait for the buzzing sound to do its work. But the magic behind ultrasonic cleaning isn’t just the machine or the sound waves—it’s the chemistry suspended in the liquid. The makeup of the ultrasonic cleaning solution determines whether cavitation bubbles form correctly, whether oils and grime release from surfaces, and whether delicate materials remain unharmed.

Ultrasonic cleaning relies on a physical phenomenon, but that physics only performs at full capacity when the solution is properly formulated. Using plain water, for example, often leads to inconsistent cavitation and poor cleaning results. Water alone lacks the surfactant and chemical structure needed to break the surface tension of contaminants, dissolve oils, or suspend particles once they detach from the item. Without the right chemistry, cavitation bubbles collapse weakly, residues reattach to surfaces, and the cleaning process slows down or fails altogether.

A well-formulated ultrasonic cleaning solution solves all of these problems simultaneously. It allows cavitation to work efficiently, prevents soil from redepositing, protects metal surfaces from corrosion, and ensures that both organic and inorganic contaminants break down quickly. In other words, the composition of the solution determines whether ultrasonic cleaning is simply “good enough” or truly high-performance.

Laboratory Glassware

Different industries depend heavily on specialized ultrasonic solutions because each type of contamination behaves differently. Oils require solvents or degreasers to break apart their molecular bonds. Mineral buildup must be tackled with chelating agents that bind to metal ions. Protein residues, such as blood or saliva, only dissolve properly when enzymatic agents are present to break down biological matter. Jewelry, dental tools, carburetors, circuit boards, 3D printed parts, laboratory glassware, and even musical instruments all need solutions tailored to their material composition and contamination type.

This means that an ultrasonic cleaning solution is not a single fixed formula but a carefully engineered combination of ingredients. These ingredients must balance several opposing demands: strong enough to remove stubborn soils, gentle enough to preserve the material, stable enough to survive cavitation, and safe enough for repeated use. Most formulations revolve around a base of water blended with surfactants, chelating agents, degreasers, corrosion inhibitors, and sometimes enzymes. Each component plays a role in shaping how cavitation behaves and how contaminants detach from surfaces.

Another reason the composition matters is surface tension. Ultrasonic machines generate cavitation bubbles, but those bubbles cannot form or collapse forcefully if the surface tension of the liquid is too high. This is where surfactants come in. By lowering surface tension, they allow cavitation bubbles to grow and collapse more efficiently, releasing energy strong enough to lift microscopic debris. Without this adjustment, even a strong ultrasonic machine can feel weak or ineffective.

Material compatibility is equally important. Different metals, plastics, alloys, and coatings react differently to acids, alkalines, solvents, and enzymes. A solution designed for stainless steel might corrode aluminum. A formula ideal for carburetor cleaning could damage acrylic or resin. A jewelry-friendly neutral solution might not cut through heavy grease in a workshop or automotive setting. Understanding what ultrasonic cleaning solutions are made of helps users choose a formula that supports both safety and performance.

As people rely more on ultrasonic cleaners for delicate items—retainers, glasses, surgical tools, watches, and electronics—the importance of using the right solution becomes even more obvious. What’s inside the liquid determines not only how well things get cleaned but also how long the items stay in good condition. Poorly chosen chemicals can dull finishes, cloud plastics, weaken adhesives, and discolor metals.

The Science Behind Ultrasonic Cleaning

Ultrasonic cleaning looks effortless from the outside, but everything happening beneath the water’s surface follows precise physical and chemical principles. To understand why the composition of an ultrasonic cleaning solution matters so much, it’s helpful to take a closer look at how cavitation works and why chemistry works hand in hand with ultrasonic energy.

Ultrasonic cleaners operate by sending high-frequency sound waves—typically 20 kHz to 200 kHz—into a liquid-filled tank. These sound waves travel through the solution and create alternating high-pressure and low-pressure cycles. During the low-pressure phase, tiny vacuum pockets begin to form in the liquid. These pockets are known as cavitation bubbles. They are microscopic, often too small to see even at close range, but they are the key to ultrasonic cleaning.

The Principle Behind Ultrasonic Cleaning

During the next phase of the sound wave, the pressure increases rapidly. The cavitation bubbles collapse with enormous force, releasing bursts of energy directly against the contaminated surface. The moment these tiny implosions occur, they produce a scrubbing effect powerful enough to lift away particles, oils, residues, and biofilm—even from areas no brush or cloth can reach. This is why ultrasonic cleaning excels at cleaning crevices, blind holes, narrow passages, threads, and textured surfaces.

However, cavitation does not happen optimally in just any liquid. The solution must allow bubbles to form easily and collapse forcefully. Water alone can form bubbles, but not efficiently. Pure water has relatively high surface tension, meaning bubbles form reluctantly and collapse with less intensity. This can severely limit the cleaning ability of an ultrasonic machine, making it appear weak even if the equipment itself is working perfectly.

This is where ultrasonic cleaning solution plays a critical role. Surfactants added to the solution reduce surface tension, allowing bubbles to form readily and distribute evenly throughout the tank. Lower surface tension also ensures that bubbles collapse with greater energy, leading to faster and more thorough cleaning. The chemical structure of the surfactant—whether anionic, nonionic, or amphoteric—affects how soils detach and disperse in the liquid.

Beyond cavitation efficiency, cleaning chemistry influences how contaminants dissolve, break apart, or suspend in the solution. Oils and greases require solvents or degreasers to break their molecular bonds and keep them separated from the surface. Mineral deposits bind to metals unless chelating agents intercept and neutralize metal ions. Biological residues such as saliva, blood, or protein films only dissolve efficiently when enzymatic agents break them down into simpler molecules.

If the ultrasonic solution doesn’t match the type of contamination, even strong cavitation may not fully remove the soil. A carburetor covered in engine oil needs a degreasing formula. Dental tools coated with protein residue need enzymatic cleaners. Jewelry with tarnish requires a specific pH range and metal-safe inhibitors. Each of these scenarios demands a different chemical composition inside the ultrasonic tank.

The pH level of the solution influences cavitation too. Acidic solutions remove oxides and mineral scale. Neutral solutions protect delicate metals, gemstones, and plastics. Alkaline solutions strip oils, soot, wax, and organic grime. Different materials respond differently to these pH environments. Aluminum can corrode in strong alkaline liquids, while brass may darken in acidic formulas. That is why specialized ultrasonic solutions exist for everything from dental retainers to precision machined components.

Temperature also influences the relationship between chemistry and cavitation. Warm solutions reduce viscosity and speed up chemical reactions, but excessive heat can suppress cavitation because bubbles form too easily and lose their implosive force. Many ultrasonic solutions are optimized to work between 40°C and 60°C, but delicate plastics or adhesives must stay below 35°C to avoid damage. Again, chemistry determines how effectively ultrasonic energy interacts with the solution.

In short, ultrasonic cleaning is a partnership between physics and chemistry. Cavitation provides the mechanical force, while the cleaning solution controls bubble behavior and dissolves contamination. Without the right chemical composition, the bubbles cannot do their job effectively, and contaminants either remain attached or re-deposit onto the surface.

The Core Components of Ultrasonic Cleaning Solutions

Ultrasonic cleaning solutions come in many varieties, yet almost all of them share a similar foundation. Although the formulas differ depending on the application—jewelry, carburetors, medical tools, optics, laboratory glassware, electronics, dental appliances, and more—the core ingredients remain consistent. Each component plays a specific role in shaping how the solution behaves under ultrasonic energy and how well it removes particular contaminants.

At the heart of every ultrasonic cleaning solution is water, typically purified or distilled to prevent mineral interference. Water serves as the solvent that carries all other ingredients, but by itself it cannot handle complex contaminants. Ultrasonic cavitation does occur in pure water, but not with enough strength or consistency to remove oils, proteins, or mineral deposits effectively. This is why water must be combined with additional components.

Cleaning agent

One of the most important categories of ingredients is surfactants. Surfactants reduce surface tension, allowing cavitation bubbles to form and collapse more efficiently. They coat soil particles, making them easier to lift and suspend in the liquid. Without surfactants, contaminants would simply cling to the surface or fall back onto the part after cleaning. Most ultrasonic solutions rely on a blend of surfactants to balance cleaning power, material safety, and residue control. The type of surfactant—anionic, nonionic, or amphoteric—also determines whether the solution is better for oils, organic debris, or delicate surfaces.

To further enhance cleaning power, many formulations include builders, which help maintain the solution’s alkalinity (for degreasing), loosen stubborn grime, and improve the efficiency of surfactants. Builders often work hand in hand with chelating agents, another essential component. Chelators, such as EDTA or sodium citrate, bind to metal ions like calcium, magnesium, or iron. These ions often interfere with cleaning by causing soap scum, water hardness deposits, or re-deposition of soil. Chelating agents prevent these issues and keep contaminants dissolved or suspended until they can be rinsed away.

For contaminants related to oils, greases, lubricants, and hydrocarbons, ultrasonic solutions often include solvents or degreasers. These can range from mild organic solvents like glycol ethers to carefully formulated blends that dissolve grease without harming metals or plastics. The concentration of solvents must be precisely balanced; too little and the oils remain stubbornly attached, too much and they may damage sensitive surfaces or reduce cavitation.

Certain industries require ultrasonic cleaners to remove biological contaminants—blood, saliva, food proteins, starches, or cellular debris. For these applications, solutions may contain enzymes, such as protease, amylase, or lipase. Enzymatic cleaners break down biological material into smaller molecules that are easier to lift and dissolve. This is essential in medical, dental, and food-processing environments where internal passages, hinges, or textured surfaces can trap organic residue.

Because ultrasonic cleaning can expose metals to water and oxygen for extended periods, many solutions include corrosion inhibitors. These ingredients form a protective barrier on metal surfaces, preventing rust, discoloration, or pitting during and after cleaning. Corrosion inhibitors are critical for steel tools, brass components, automotive parts, and any metal prone to oxidation.

Finally, many ultrasonic cleaning solutions contain pH stabilizers, anti-foaming agents, and rinsing aids. pH stabilizers ensure the solution remains effective throughout its lifespan, even as contaminants accumulate. Anti-foaming agents prevent excessive bubbles that can interfere with cavitation. Rinsing aids help ensure that once the cleaning cycle is finished, the item emerges free from residues and dries without streaks or spots.

These ingredients form the backbone of most ultrasonic cleaning formulations, creating a solution that supports strong cavitation, dissolves contaminants, and protects sensitive materials. Understanding these components provides a foundation for exploring how each class of ingredient functions in more detail—beginning with surfactants, the true workhorses of ultrasonic cleaning chemistry.

Surfactants: The Key Ingredient That Makes Everything Work

Surfactants are the quiet engine inside every effective ultrasonic cleaning solution. They may not look impressive on a label, but they are the ingredient that makes ultrasonic cleaning dramatically more powerful than plain water. If cavitation is the physical force that knocks debris loose, surfactants are the chemical agents that help separate soil from the surface and keep it suspended so it cannot reattach.

A surfactant molecule has two sides: one that is attracted to water and one that is attracted to oils or organic grime. This dual nature allows surfactants to insert themselves between contaminants and the surface of the item being cleaned. Once the surfactant molecules surround the soil particles, they lift them away and hold them in suspension. Without this coating effect, dirt and oils would simply float around in the tank and settle back onto the item as soon as the ultrasonic cycle slows down.

The role of surfactants in ultrasonic cleaning goes far beyond basic soil removal. They drastically reduce the surface tension of the liquid, making it easier for cavitation bubbles to form and collapse. This is essential, because cavitation can only generate its characteristic micro-scrubbing effect when bubbles form freely and are distributed uniformly throughout the tank. High surface tension—like that of pure water—acts like a barrier that prevents efficient bubble formation. Surfactants lower that barrier and open the door for strong, energetic cavitation.

Different types of surfactants behave differently, and ultrasonic cleaning solutions often contain a blend tailored to the specific cleaning task.

Anionic surfactants are common in stronger alkaline solutions. They excel at breaking apart oils, greases, and organic debris. Their negatively charged heads repel each other in water, allowing them to spread rapidly across surfaces. These surfactants are often used in industrial degreasers, automotive part cleaners, and heavy-duty maintenance solutions.

Nonionic surfactants are more gentle and versatile. They lack an electrical charge, which makes them stable across a wide range of pH levels and temperatures. Their mild behavior makes them ideal for cleaning delicate items such as jewelry, glasses, laboratory glassware, dental appliances, electronics, and other materials that cannot tolerate strong chemical action. Nonionic surfactants are also excellent wetting agents, enhancing cavitation in solutions designed for precision cleaning.

Amphoteric surfactants switch their charge depending on the pH of the solution. This adaptability gives them a unique advantage: they can remain stable and effective whether the solution is acidic, neutral, or alkaline. Amphoteric surfactants provide a balance of cleaning power and material safety, making them suitable for mixed-material assemblies or items with sensitive coatings.

The concentration of surfactants in an ultrasonic cleaning solution is another critical factor. Too little surfactant makes the solution weak and inefficient. Too much creates excessive foam, which disrupts cavitation and reduces cleaning performance. This is why high-quality ultrasonic solutions are formulated with precise ratios that maintain strong cleaning activity without interfering with the ultrasonic process.

Surfactants also influence how soils behave after removal. A well-formulated solution prevents oils or particles from clumping together or settling at the bottom of the tank. Instead, contaminants remain suspended until they are rinsed away, which ensures that cleaned items emerge spotless. This “soil suspension” property is especially important in ultrasonic cleaning because the constant agitation of the tank can easily redeposit particles if they’re not chemically stabilized.

Industries relying on ultrasonic cleaning choose different surfactant blends depending on the items they clean. Automotive shops require strong anionic surfactants for removing oil and carbon buildup. Optical labs prefer low-foam, nonionic surfactants that leave glass and lenses streak-free. Medical and dental environments often use amphoteric or nonionic surfactants that are compatible with enzymatic formulas and safe for stainless steel instruments.

Chelating Agents and Builders

Chelating agents and builders are some of the most important supporting ingredients in ultrasonic cleaning solutions, even though they rarely get the attention that surfactants or solvents receive. Their role is subtle but essential: they ensure that the liquid environment remains stable, effective, and free from interference that would weaken cleaning power. Without chelators and builders, even the strongest surfactant blend would struggle to produce consistent results.

Chelating agents work by binding to metal ions that float freely in the solution. These metal ions, especially calcium and magnesium from hard water, interfere with cleaning performance. They react with surfactants, forming insoluble residues that either stick to surfaces or settle as gritty deposits at the bottom of the ultrasonic tank. Over time, this reduces cavitation efficiency and leaves items with cloudy films or mineral stains. Chelators prevent this problem by capturing the metal ions and holding them in solution so they cannot cause trouble.

One of the most widely used chelating agents in ultrasonic cleaning solutions is EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). EDTA has a strong affinity for metal ions and can bind to them quickly and effectively. Other common chelators include sodium citrate, which is milder and better suited for neutral or slightly alkaline solutions, and gluconates, which offer excellent compatibility with metals and sensitive materials. These chelators ensure that minerals do not form deposits on jewelry, lenses, dental tools, or automotive parts during cleaning.

Builders often work alongside chelating agents but serve additional purposes. Builders help maintain the alkaline conditions necessary for breaking down oily or greasy contaminants. They enhance the performance of surfactants by softening the water, reducing interference, and improving soil suspension. By keeping the pH stable, builders allow the solution to maintain optimal cleaning strength throughout multiple ultrasonic cycles.

Strong alkaline builders like sodium carbonate or sodium metasilicate boost cleaning power for industrial oils, carbon residue, or engine parts. These ingredients increase the pH of the solution, helping break down hydrocarbons and stubborn organic deposits. However, because high alkalinity can damage aluminum, brass, and certain plastics, these builders are used primarily in industrial degreasers rather than general-purpose formulas.

Milder builders such as sodium bicarbonate or sodium phosphate offer balanced cleaning power. They break down light oils, remove residues, and support surfactant activity without posing a risk to delicate items. Builders also prevent soil from reattaching to the surface by ensuring it stays suspended in the solution long enough to be rinsed away.

Chelating agents and builders are essential in environments where water hardness is unpredictable. In regions with high mineral content in tap water, ultrasonic cleaners without chelators quickly develop scale deposits inside the tank. These scale deposits reduce ultrasonic efficiency by absorbing energy and interfering with cavitation. Proper chelation stops this from happening, extending the life of both the cleaner and the solution.

Another important benefit of chelating agents is their ability to protect metals from unwanted reactions. By binding reactive ions, they prevent discoloration, pitting, or tarnishing on metals such as brass, copper, and stainless steel. This protection is crucial for jewelry cleaning, instrument sterilization, and automotive maintenance, where the integrity of metal surfaces must be preserved.

Chelators also work with solvents to improve degreasing performance. Heavy oils and lubricants often contain additives that include metal-based compounds. Chelating agents neutralize these compounds so that solvents and surfactants can dissolve the oily matrix more efficiently. This chemical synergy is one of the reasons ultrasonic cleaning works so well for carburetors, engine parts, and industrial tools.

Builders complement this process by stabilizing the cleaning environment. When surfactants begin to weaken or soil loads increase, builders maintain the necessary pH and water-softening action to ensure the solution doesn’t lose effectiveness too quickly. This enables longer bath life, fewer solution changes, and more predictable results.

Solvents and Degreasers in Ultrasonic Solutions

Among all the components found in ultrasonic cleaning solutions, solvents and degreasers are the ones most responsible for handling the toughest, most stubborn contaminants—oils, lubricants, waxes, greases, carbon residue, machining fluids, and other hydrocarbons. These contaminants resist water, cling aggressively to surfaces, and often seep into tiny gaps or textured areas where brushes and cloths cannot reach. In ultrasonic cleaning, solvents act as the chemical muscle that partners with cavitation to loosen and disintegrate oily films at the molecular level.

The most common solvents in water-based ultrasonic cleaning solutions are glycol ethers, a family of compounds known for their ability to dissolve both water-soluble and oil-soluble soils. Glycol ethers such as dipropylene glycol monomethyl ether or ethylene glycol butyl ether are strong enough to break apart grease and fuels, yet gentle enough to protect plastics, paints, and metals when properly diluted. Their versatility makes them a popular choice in automotive, industrial, and electronic cleaning applications.

Another group of solvents used in ultrasonic solutions includes mild alcohols like isopropanol or ethanol. These solvents evaporate quickly, penetrate oil films effectively, and help reduce drying time after ultrasonic cleaning. Alcohol-based solvents are often included in formulas for optical equipment, electronic components, and fine mechanical parts, where residue-free drying is essential. However, the concentration of alcohol must remain controlled, because high levels can interfere with cavitation or damage adhesives and soft plastics.

For heavier industrial applications, ultrasonic solutions may contain terpenes, which are natural solvents derived from plants such as citrus. D-limonene, for example, is an effective degreaser widely used for removing sticky residues, adhesives, tar, and carbon black from parts. Terpenes offer strong solvent action and a more environmentally friendly alternative to petroleum-based solvents, but they must be balanced carefully to avoid surface softening or sensitivity reactions.

Petroleum distillates are rarely used in modern ultrasonic cleaning due to safety concerns and incompatibility with water-based systems. Today’s formulations focus primarily on water-soluble solvents that maintain cavitation efficiency while offering strong degreasing performance. Regardless of the specific solvent used, the goal is always the same: to break down oily films so cavitation can lift them away.

Solvents enhance ultrasonic cleaning in several important ways. First, they reduce the viscosity of oils, making them easier to dislodge. Thick lubricants and greases that would normally resist agitation become more fluid when exposed to solvent molecules. This lower viscosity allows cavitation bubbles to penetrate deeply into the contaminant layer and release it more completely.

Second, solvents reduce the interfacial tension between oil and water, helping oils emulsify instead of floating as a slick on the surface of the tank. If oils float freely, they can reattach to parts during rinsing. By creating a stable emulsion, solvents ensure that oils remain dispersed and suspended until the solution is replaced.

Third, solvents work synergistically with surfactants and builders. While surfactants surround and lift soil particles, solvents dissolve the matrix holding them together. Builders stabilize the pH and support the action of both solvents and surfactants. This chemical cooperation is what makes ultrasonic cleaning so effective for degreasing.

Not all solvents are safe for all surfaces. Certain plastics, such as polycarbonate or ABS, may swell or crack when exposed to strong solvents. Rubber components, seals, and adhesives can degrade if the solvent concentration is too high. This is why ultrasonic cleaning solutions are carefully formulated: they must deliver strong degreasing power without compromising the integrity of the materials being cleaned.

For this reason, industrial ultrasonic solutions often specify material compatibility in their datasheets, especially for aerospace, automotive, and precision manufacturing. Jewelry cleaning formulas avoid strong solvents to protect stones and delicate alloys. Electronics-safe solutions use solvents with low residue and low conductivity to prevent circuit damage.

Enzymatic Ultrasonic Cleaning Solutions

Not all contaminants are oily, metallic, or mineral-based. In many industries—including medical, dental, food processing, orthodontics, laboratory science, and even certain manufacturing sectors—the primary type of contamination is biological. These contaminants include proteins, blood, saliva, fats, starches, and other organic materials that do not dissolve easily in water or respond well to simple degreasers. This is where enzymatic ultrasonic cleaning solutions become indispensable.

Enzymes are biological catalysts—special proteins that accelerate specific chemical reactions. In cleaning solutions, enzymes target and break down organic soils into smaller, more manageable molecules that can be lifted, dissolved, or suspended in the liquid. Ultrasonic cleaners enhance enzymatic activity by providing mechanical agitation, while enzymes enhance ultrasonic cleaning by breaking down debris that cavitation alone cannot remove efficiently.

There are three primary types of enzymes used in ultrasonic cleaning solutions, each designed to attack a different class of biological contaminants.

Protease enzymes are the most widely used because proteins are the most common form of organic contamination on medical and dental tools. Blood, tissue fragments, food particles, saliva film, and biofilm residues all contain protein structures. Protease enzymes break down the peptide bonds between amino acids, essentially unzipping proteins into smaller molecules that cavitation can dislodge easily. This is crucial for cleaning instruments with hinges, serrated edges, lumens, or micro-grooves where proteins tend to accumulate.

Amylase enzymes specialize in breaking down starches. Starches are common in food-handling environments, orthodontic appliances, and laboratory glassware used for biological experiments. Starch residues often form sticky films that water alone cannot penetrate. Amylase converts starch molecules into sugars, which then dissolve more easily during ultrasonic agitation.

Lipase enzymes target fats and oils of biological origin—body oils, fat deposits, and lipid-based films. Although lipase enzymes are sometimes used alongside degreasing agents, they are especially valuable when cleaning items that cannot be exposed to harsh solvents or alkaline formulas, such as dental retainers, surgical tools, and certain polymers.

Some advanced ultrasonic cleaning solutions combine all three enzyme types into a multi-enzymatic formula. These are especially common in hospital and dental sterilization workflows, where thorough pre-cleaning is essential before instruments enter autoclave sterilization. Multi-enzymatic cleaners provide broad-spectrum activity that reduces the risk of cross-contamination, improves hygiene, and enhances the lifespan of delicate instruments.

Enzymatic ultrasonic solutions are typically neutral or near-neutral in pH. This ensures compatibility with stainless steel instruments, surgical-grade plastics, flexible endoscopes, acrylics, silicone, and composite materials. A neutral pH also preserves the activity of the enzymes, which can be sensitive to strong acids or alkalines. This makes enzymatic formulas some of the safest and most versatile ultrasonic cleaning solutions available.

Temperature plays a particularly important role in enzymatic cleaning. Most enzymes perform best within a warm, but moderate, temperature range—usually between 35°C and 55°C. Below this range, enzymes slow down and become less effective. Above it, they begin to denature, losing their structure and activity. Ultrasonic cleaners with temperature control often include presets designed specifically for enzymatic cycles, balancing enzyme activity with optimal cavitation performance.

Another advantage of enzymatic solutions is their ability to penetrate biofilms. Biofilms are complex layers of microorganisms embedded in a protective matrix of proteins and polysaccharides. They are notoriously difficult to remove and are a major concern in both medical and food-processing contexts. Enzymes help break down the structural components of biofilm, allowing cavitation bubbles to lift the microbial layer more effectively.

Because enzymatic solutions are formulated for gentle yet thorough cleaning, they are widely used for delicate items that require a high standard of hygiene without the risk of corrosion or surface damage. Dental aligners, orthodontic retainers, surgical instruments, tattoo equipment, lab pipettes, and precision medical devices all benefit from enzymatic ultrasonic cleaning.

However, enzymatic solutions are not suitable for every situation. They are less effective on heavy grease, carbon deposits, and mineral scale. They also require proper handling and disposal, as they are biologically active compounds. For these types of soils or industrial applications, alkaline or solvent-based ultrasonic solutions are more appropriate.

pH Levels and What They Mean

The pH of an ultrasonic cleaning solution influences nearly every aspect of its behavior, from how effectively it dissolves contaminants to how safely it interacts with metals, plastics, coatings, gemstones, and electronic components. While the ingredients inside the solution determine its chemical makeup, pH determines its overall personality—whether it behaves gently, aggressively, or somewhere in between.

Understanding pH is critical because ultrasonic cleaning is not a universal process. A solution that performs beautifully on stainless steel tools may cause damage to aluminum components. A formula that dissolves grease effortlessly might discolor brass or copper. Similarly, a gentle neutral solution that provides excellent results for jewelry may barely touch the heavy carbon residue inside an engine part. Recognizing how pH shapes these cleaning differences is essential for using ultrasonic cleaning safely and effectively.

Ultrasonic cleaning solutions can be broadly divided into three pH categories: acidic, neutral, and alkaline. Each type has advantages, limitations, and specific application areas.

Acidic Ultrasonic Solutions

Acidic solutions fall below 7 on the pH scale, and their strength varies widely depending on the application. Mild acids—such as citric acid or diluted organic acids—are commonly used to remove mineral deposits, oxidation, rust stains, and scale. These solutions are especially effective on items affected by hard-water buildup. Instruments with lime stains, engine parts with oxidation, and parts exposed to mineral-rich environments all benefit from acidic ultrasonic solutions.

More aggressive acidic formulas exist for industrial descaling or heavy oxide removal, though these are rarely used for delicate items. Strong acids can attack metals like aluminum, zinc, magnesium, and brass, so they must be used with great care. Acid-based ultrasonic solutions are generally not suitable for jewelry with soft stones, items with protective coatings, or components with solder joints.

For many users, mild citric-acid-based formulas provide a good balance—they remove oxidation without causing harsh corrosion and remain compatible with many stainless steel components.

Neutral Ultrasonic Solutions

Neutral solutions hover around a pH of 6 to 8 and are the most versatile category. These solutions are formulated for delicate, mixed-material items that could be damaged by acids or alkalines. Neutral ultrasonic solutions often contain nonionic surfactants, mild wetting agents, and sometimes enzymes. They are typically used in dental offices, laboratories, jewelry shops, and electronics repair environments.

Neutral cleaners are ideal for:

- Jewelry with gemstones

- Eyeglasses and optics

- Dental aligners and retainers

- Watches and mechanical assemblies

- Electronic boards (when designed for aqueous cleaning)

- Stainless steel surgical tools

- Plastics, acrylics, and resins

Because neutral solutions do not aggressively attack materials, they are considered the safest all-purpose option. They offer enough cleaning power for most household and professional applications while minimizing risk.

Alkaline Ultrasonic Solutions

Alkaline solutions register above 8 on the pH scale and are the strongest category in terms of cleaning power. These formulas excel at removing oils, grease, wax, soot, and carbon-based residue. They often contain surfactants, builders, chelating agents, and degreasers that work synergistically to break apart organic films.

High-alkaline ultrasonic solutions are widely used in:

- Automotive and industrial maintenance

- Carburetor and engine part cleaning

- Machining shops

- Metalworking and fabrication

- Restoration and reconditioning

Alkaline solutions can be extremely effective, but they are not universally safe. They may discolor or corrode aluminum, brass, copper, and zinc alloys if not formulated with corrosion inhibitors. Strong alkaline solutions can also damage certain plastics, paints, and coatings.

Moderate alkalines, however, strike a balance—they are powerful enough to remove oils while remaining safe for stainless steel, glass, and many industrial materials.

How pH Interacts with Ultrasonic Cavitation

pH does more than determine what contaminants the solution can dissolve—it also affects cavitation behavior. In general:

- Neutral solutions provide stable, consistent cavitation suitable for precision cleaning.

- Alkaline solutions promote strong cavitation and aggressive cleaning action.

- Acidic solutions may suppress cavitation slightly but provide essential chemical reactions for scale removal.

Choosing the correct pH is therefore a matter of both material compatibility and cleaning performance.

Selecting the Right pH for Your Application

Selecting a pH is not about choosing the “strongest” cleaner but the “right” one. A powerful alkaline solution may destroy an acrylic retainer or discolor brass jewelry. Similarly, a neutral solution may be too gentle for heavy engine oils. The key is matching pH to both the contaminant and the material.

Corrosion Inhibitors and Material Protection

Metal components face a unique challenge during ultrasonic cleaning. Although ultrasonic cavitation is extremely effective at removing soils, it also subjects metal surfaces to prolonged contact with water, oxygen, and cleaning agents. This exposure creates ideal conditions for corrosion, discoloration, tarnish, or pitting if the solution is not properly formulated. To counter these risks, ultrasonic cleaning solutions often include corrosion inhibitors, a critical class of additives that protect metal surfaces while allowing strong cleaning action to take place.

Corrosion inhibitors work by forming a microscopic protective film on the surface of the metal. This layer does not interfere with cavitation or cleaning chemistry, but it shields the surface from oxidative reactions. Without inhibitors, metal parts can begin to rust or tarnish even during a single ultrasonic cycle, particularly if they are made from iron-rich alloys or reactive metals such as brass and copper.

One of the most common metals cleaned ultrasonically is stainless steel. While stainless steel is naturally corrosion-resistant due to its chromium oxide layer, improper cleaning chemicals can weaken that protective film. Solutions that include chlorides, strong acids, or improperly balanced alkaline agents can trigger pitting corrosion or discoloration. Corrosion inhibitors designed for stainless steel prevent this by reinforcing the passive oxide layer and ensuring that the surface remains intact throughout the cleaning process.

Brass and copper are especially vulnerable to oxidation and discoloration. Acidic solutions can remove tarnish effectively, but they may also attack the underlying metal if inhibitors are not present. To avoid pinking, darkening, or dullness, specialized inhibitors are added to protect copper-alloy surfaces. These additives prevent rapid oxidation while still allowing the acid to dissolve unwanted corrosion products.

For more sensitive metals such as aluminum and zinc, corrosion inhibitors become essential. Both metals react quickly with alkalines and even some neutral solutions. Aluminum in particular is known for forming a protective oxide layer that is easily disrupted. When contacted by a strong alkaline cleaning agent, aluminum can develop gray patches, pitting, or a chalky surface texture. Corrosion inhibitors for aluminum work by buffering the solution and creating a stabilizing barrier that prevents metal loss, even during aggressive cleaning cycles.

Carbon steels and tool steels, commonly found in automotive parts, manufacturing tools, and machine shop components, also benefit significantly from corrosion inhibitors. Without protection, the combination of heat, moisture, and cavitation can trigger flash rust—rapid oxidation that appears within minutes after cleaning. Inhibitors prevent this by stabilizing the metal surface and suppressing oxidation during and after ultrasonic cleaning.

Some ultrasonic cleaning solutions even contain volatile corrosion inhibitors (VCIs), which create a protective vapor around the metal item as it dries. This prevents corrosion during storage once the cleaning process is complete. VCIs are often used for firearms, aerospace components, and precision-machined parts where even slight oxidation can affect performance.

Besides preventing oxidation, corrosion inhibitors also contribute to material preservation. Many items that undergo ultrasonic cleaning include coatings, platings, or decorative finishes. Watches, jewelry, dentures, retainers, surgical tools, and musical instrument components may all feature sensitive surfaces that cannot tolerate chemical attack. Inhibitors ensure that these finishes remain intact and retain their original luster.

Another benefit is bath stability. As contaminants accumulate in the ultrasonic tank, the chemical balance may shift. Corrosion inhibitors help maintain stability, preventing unexpectedly aggressive reactions as the solution ages. This contributes to longer bath life and more predictable cleaning results.

Importantly, corrosion inhibitors must be compatible with all other components of the cleaning solution. A formula that includes surfactants, chelators, builders, solvents, and enzymes must integrate corrosion inhibitors in a way that does not interfere with cavitation or cleaning efficiency. High-quality formulations achieve this balance through careful chemical engineering.

Corrosion protection is especially crucial in professional settings such as dental clinics, machine shops, laboratories, and electronics repair centers. In these environments, equipment longevity directly affects reliability and cost efficiency. Improper cleaning solutions may damage delicate tools or compromise metal precision components, leading to premature wear or failure.

Additives for Rinsing, Defoaming, and Stability

While surfactants, solvents, enzymes, and corrosion inhibitors tend to steal the spotlight in ultrasonic cleaning chemistry, the performance and reliability of the solution also depend heavily on a group of supporting additives. These additives—rinsing agents, defoamers, stabilizers, and bath-life extenders—work quietly in the background to ensure that the ultrasonic cleaning process runs smoothly, consistently, and safely. Without them, even the best cleaning formulas could suffer from inconsistent cavitation, foaming disruptions, or rapid degradation.

Anti-Foaming Agents

Foam is the natural enemy of ultrasonic cleaning. Many surfactants produce foam, especially when agitated, and ultrasonic cavitation is a form of intense microscopic agitation. When foam builds up on the surface of the liquid, it traps energy that would otherwise travel through the bath. Foam acts like a cushion, absorbing ultrasonic waves and preventing them from penetrating the tank effectively. This reduces cavitation strength and creates uneven cleaning zones.

Anti-foaming agents, also known as defoamers, prevent this problem by weakening the surface film that stabilizes bubbles. Common defoamers include silicone emulsions, fatty alcohols, and certain mineral oil derivatives. These compounds spread across the surface of the bath, breaking apart foam before it becomes a barrier. High-quality ultrasonic solutions must strike a careful balance: they need surfactants to reduce surface tension and improve cleaning, but they must prevent those surfactants from producing excessive foam.

Defoamers also improve tank visibility, making it easier for technicians to monitor parts during cleaning. In industrial environments with long cleaning cycles, maintaining a low-foam bath is essential for consistent performance.

Rinse Aids and Wetting Agents

Rinse aids are additives that help the cleaned surface shed water more easily. After the ultrasonic cycle, parts must be rinsed to remove loosened contaminants and chemical residues. If the water clings to the surface or forms droplets, it can leave spots, streaks, or mineral marks—especially on glass, stainless steel, jewelry, lenses, or polished metals.

Rinse aids reduce water adhesion by altering droplet surface tension. Instead of beading, water forms a thin, even film that drains away quickly. This helps parts dry faster and more cleanly. Optical labs, dental offices, and jewelry workshops often rely on solutions with rinse aids to ensure pristine clarity and high-quality finishes on delicate items.

Bath Stabilizers

Stabilizers maintain the chemical balance of the solution over time. As contaminants accumulate in the tank—oils, metal particles, biological debris, or dissolved minerals—the pH, surfactant balance, or solvent ratio may begin to shift. Without stabilizers, this gradual change could reduce the cleaning effectiveness long before the solution is visibly dirty.

Common stabilizers include buffering agents, oxidation inhibitors, and compounds that slow the degradation of surfactants or enzymes. These ingredients ensure that the cleaning solution maintains peak performance through repeated ultrasonic cycles, extending bath life and maintaining predictable cleaning results.

Stabilizers are especially important in:

- Medical and dental environments

- Automotive and industrial cleaning applications

- Laboratory and research settings

- High-load production facilities

In these domains, cleaning quality must remain consistent across multiple cycles, and stabilizers are crucial for that reliability.

Emulsifiers and Soil Suspension Agents

Once contaminants are lifted from the surface, they must remain suspended in the solution until rinsed away. Otherwise, they can redeposit onto the cleaned item during or after the cycle. Soil suspension agents, sometimes referred to as emulsifiers, perform this critical function. They surround particles, oils, or dissolved soils and keep them dispersed throughout the bath.

These additives prevent:

- Reattachment of oils

- Particulate streaking on surfaces

- Cloudy films on plastics or glass

- Heavy sludge accumulation in the tank

Suspension agents also make it easier to dispose of used cleaning solutions, as contaminants remain evenly distributed rather than forming sticky clusters.

Preservatives and Anti-Microbial Agents

Some ultrasonic cleaning formulas include small amounts of preservatives to inhibit bacterial growth, especially in solutions designed for long-term storage or reuse. While these additives are different from disinfectants or sterilizing agents, they prevent the solution from becoming cloudy or foul-smelling over time.

Preservatives are commonly used in:

- Multi-enzymatic medical cleaners

- Neutral jewelry-safe solutions

- Precision optical cleaners

These additive systems help maintain clarity, odor control, and chemical reliability.

Why Additives Matter

Although these additives may account for only a small percentage of the total formula, they have an outsized impact on cleaning quality. Without defoamers, cavitation is reduced. Without rinse aids, surfaces dry unevenly. Without stabilizers, the solution loses strength prematurely. Without emulsifiers, soils redeposit. Each additive supports the ultrasonic process and ensures a predictable, professional result across a wide range of applications.

The Differences Between Consumer and Industrial Ultrasonic Solutions

Not all ultrasonic cleaning solutions are created for the same purpose. The chemical composition, strength, pH range, and additives in a solution vary depending on whether the product is designed for home use, professional environments, or heavy industrial applications. Understanding the difference between consumer and industrial ultrasonic solutions is crucial for selecting a formula that performs well without damaging the item being cleaned.

Consumer Ultrasonic Cleaning Solutions

Consumer ultrasonic solutions are formulated for safety, simplicity, and broad compatibility. They are designed to work well with a wide variety of household items, including jewelry, eyeglasses, dental appliances, small tools, coins, watchbands, and everyday metal accessories. Most consumer formulas are neutral or mildly alkaline, avoiding harsh acids or corrosive agents that could damage delicate items.

These solutions prioritize:

- Material safety for plastics, soft metals, gemstones, coatings, and enamels

- Low foaming characteristics suitable for small tabletop ultrasonic machines

- Ease of use, requiring minimal dilution or preparation

- Compatibility with stainless steel tanks and home-grade transducers

- Pleasant or neutral scent, making home cleaning more comfortable

- Short cycle efficiency, cleaning effectively in 3 to 10 minutes

Consumer-grade solutions typically contain mild surfactants, gentle wetting agents, and corrosion inhibitors. Solvents, if present, are usually low-strength and water-soluble to prevent damage to sensitive materials. These formulas avoid strong alkalinity, high acidity, and aggressive solvents.

Common applications for consumer ultrasonic solutions include:

- Jewelry (including soft stones like pearls and opals when using the right formula)

- Eyeglasses, sunglasses, and optical lenses

- Retainers, aligners, and dentures

- Electric shaver parts

- Small electronics components (only when designed for aqueous cleaning)

- Coins and collectibles

- Make-up brushes and personal care tools

In all these cases, the solution’s chemistry must be gentle enough to avoid clouding acrylics, stripping coatings, or corroding decorative metals.

Professional Ultrasonic Cleaning Solutions

Professional formulas are more powerful and specialized. They are used in dental clinics, laboratories, watchmaking shops, electronics repair centers, optical facilities, and surgical instrument departments. These solutions are engineered to remove biological contamination, precision manufacturing oils, fine particulate matter, or oxidation without harming sensitive equipment.

Professional solutions often include:

- Multi-enzymatic systems for breaking down complex biological residues

- Specialized surfactant blends for precision glass and optics

- Corrosion inhibitors compatible with medical-grade stainless steel

- Controlled pH ranges for specific instruments or materials

- Stabilizers that allow multiple cleaning cycles without degradation

They are formulated to work with ultrasonic machines that may have adjustable frequencies, larger tanks, and heated cycles. These solutions must meet strict hygiene and performance standards, especially in medical and laboratory environments where cleanliness impacts patient safety or experimental validity.

Industrial Ultrasonic Cleaning Solutions

Industrial solutions are the most powerful category. These formulas target heavy-duty contaminants like:

- Engine oil and grease

- Carbon deposits

- Cutting oils

- Machining fluids

- Soot and combustion residue

- Rust, oxidation, and scale

- Metal finishing compounds

- Industrial adhesives and sealants

Industrial ultrasonic solutions often feature:

- Strong alkaline bases

- Aggressive solvents

- Chelators designed for high mineral loads

- High-performance builders

- Strong emulsifiers for keeping heavy contaminants suspended

These solutions are suitable for:

- Automotive and engine rebuild shops

- Aerospace manufacturing

- Metal fabrication and machining

- Injection molding facilities

- Firearms cleaning

- Industrial maintenance departments

Industrial ultrasonic cleaners are typically larger, more powerful, and able to operate with heated tanks. Many industrial solutions require careful handling, proper ventilation, and specific disposal methods. They are not suitable for household or delicate materials.

Why the Differences Matter

Using the wrong type of ultrasonic cleaning solution can lead to serious damage:

- Industrial alkaline cleaners can cloud plastics or dissolve aluminum.

- Acidic descalers can strip plating or tarnish jewelry.

- Consumer solutions may be too weak for industrial soils.

- Enzymatic cleaners may not dissolve oil or carbon residue.

- Solvent-based degreasers can damage coatings or adhesives.

Selecting the correct type of solution ensures the cleaning process is effective, safe for the material, and optimized for the contaminant.

How Cleaning Solution Ingredients Affect Performance

Every ingredient inside an ultrasonic cleaning solution influences how the liquid interacts with cavitation, how contaminants break apart, and how well surfaces are protected during the cleaning process. The way these ingredients work together determines not only how effectively the solution removes soils but also how safe the cleaning environment is for delicate materials. Understanding these relationships helps users choose formulas that achieve the best results for their specific applications.

Surface Tension and Bubble Formation

One of the most fundamental ways solution chemistry affects ultrasonic performance is through surface tension. Cavitation depends on the ability of bubbles to form and collapse rapidly. High surface tension makes bubble formation more difficult, reducing cavitation strength and overall cleaning power. Surfactants lower surface tension, allowing bubbles to form more uniformly and collapse with greater force. This enhanced collapse translates directly into more effective cleaning, especially in small crevices and complex geometries.

Solutions rich in high-quality surfactants produce tighter, more evenly distributed cavitation fields. This results in faster cleaning cycles, more consistent soil removal, and better coverage throughout the tank. Conversely, a solution with poor surfactant structure will feel weak, regardless of how strong the ultrasonic machine is.

Chemical Reactions and Soil Breakdown

Different contaminants respond to different types of chemical action. Ultrasonic energy alone can loosen debris, but many soils require dissolution, emulsification, or enzymatic breakdown before cavitation can remove them fully.

For example:

- Oils respond best to solvents, emulsifiers, and alkaline builders.

- Proteins break down only when exposed to enzymatic agents like protease.

- Mineral scale requires the dissolving power of acidic chelators or organic acids.

- Carbon residue benefits from strong alkalinity and certain solvent blends.

Each contaminant has a specific chemical profile, and ultrasonic solutions are formulated to target those characteristics. When the chemistry aligns with the soil type, cavitation works at its full potential.

Emulsification and Soil Suspension

Once contaminants lift off a surface, they must remain suspended in the solution. Otherwise, they will reattach to surfaces during or after the cleaning cycle. This is especially problematic with oils, greases, and fine particulate matter.

Emulsifiers and suspension agents keep soils dispersed by surrounding them with stabilizing chemical structures. This ensures that contaminants remain separated from the cleaned item until the solution is drained or replaced.

A well-formulated solution will maintain soil suspension even during long cleaning cycles or heavy loads, preventing redeposition and keeping parts pristine.

pH and Material Compatibility

The pH of a cleaning solution dramatically affects both cleaning power and material safety. This relationship shapes performance in several ways:

- Alkaline solutions attack oils and organic residues aggressively but may corrode aluminum or oxidize brass.

- Neutral solutions provide balanced cleaning for delicate materials but may struggle with industrial contaminants.

- Acidic solutions dissolve rust, scale, and oxidation but can strip plating or damage soft metals.

Choosing the wrong pH can undermine cleaning effectiveness or harm the item being cleaned. The right pH creates the proper chemical environment for soil removal without compromising the integrity of the material.

Temperature Sensitivity and Reaction Speed

Temperature influences how quickly chemical reactions occur within the solution. Warmer solutions reduce viscosity, improve molecular movement, and accelerate cleaning activity. However, excessive heat can interfere with cavitation by allowing bubbles to form too easily without generating enough implosive force.

Most ultrasonic solutions are engineered to work best between 40°C and 60°C, though certain sensitive materials require cooler temperatures. Enzymatic cleaners are particularly temperature-sensitive; heat above 55°C can denature enzymes and reduce their effectiveness.

The combination of temperature and chemistry must therefore be carefully balanced for optimal performance.

Cavitation Stability and Additive Support

Anti-foaming agents, stabilizers, and bath-life extenders further influence ultrasonic performance by ensuring stable, predictable cavitation. Foam suppresses ultrasonic energy, while chemical instability weakens cleaning strength over time. Stabilizers ensure that ingredients maintain their structure and effectiveness, even after hours of continuous use.

A well-engineered solution maintains cavitation uniformity across the tank, allowing all surfaces of the item to receive equal cleaning intensity.

Protection Against Damage

Corrosion inhibitors, pH buffers, and material-safe surfactants work together to prevent surface damage during cleaning. Cavitation is energetic, and without chemical protection, it may accelerate oxidation or cause microscopic wear on sensitive metals. The right additives ensure that while contaminants are removed, the base material remains unharmed.

The Combined Effect

No single ingredient determines the performance of an ultrasonic cleaning solution. Instead, the combined chemical balance—surfactants, chelators, solvents, enzymes, inhibitors, stabilizers—creates the environment where cavitation can achieve maximum cleaning power. High-quality formulations reflect years of chemical engineering, ensuring that every ingredient supports both cleaning performance and material protection.

What Happens When You Use the Wrong Solution

The composition of ultrasonic cleaning solution is not just a matter of performance; it is also a matter of safety and preservation. Using the wrong solution—one designed for incompatible materials or the wrong type of contamination—can lead to results ranging from disappointing cleaning performance to irreversible damage. Because ultrasonic cavitation amplifies whatever chemistry is present in the tank, mistakes become more aggressive and visible compared to traditional soaking or manual cleaning.

Poor Cleaning Performance

The most immediate consequence of using the wrong solution is simply ineffective cleaning. If the chemical profile does not match the contaminant:

- Oils remain smeared on the surface.

- Proteins remain stuck in crevices.

- Mineral scale barely dissolves.

- Carbon deposits cling stubbornly to metal.

For example, trying to clean an engine carburetor using a mild jewelry-safe solution will produce weak or partial results. Similarly, using a neutral household ultrasonic detergent on surgical tools contaminated with dried blood will not break down the protein bonds. Cavitation alone is not enough; proper chemistry is essential.

Foaming and Cavitation Loss

Using a solution that produces excessive foam is one of the fastest ways to disrupt ultrasonic cleaning. Foam blocks ultrasonic waves and prevents cavitation from forming, which stops cleaning in its tracks. This often happens when people use:

- Dishwashing soaps

- Laundry detergents

- Hand soaps

- Household cleaners not intended for ultrasonic use

Even if these products seem gentle, their foaming properties can render the ultrasonic machine nearly useless. In severe cases, foam can overflow the tank and cause electrical hazards.

Material Damage

Perhaps the most serious risk comes from choosing an ultrasonic solution that chemically reacts with the item being cleaned. The wrong pH, solvent, or chelating agent can permanently damage metals, plastics, coatings, gemstones, and adhesives.

Here are some common examples:

- Alkaline solutions can corrode aluminum, zinc, and brass, leaving dark stains or pitting.

- Acidic solutions can remove plating, tarnish decorative finishes, or etch glass.

- Strong solvents can dissolve glues, cloud polycarbonate lenses, or weaken plastics.

- Oxidizing agents can strip color from anodized surfaces or tarnish silver.

- Chelators may discolor copper alloys by pulling metal ions out of the surface.

Ultrasonic energy accelerates these chemical reactions. A formula that might take hours to cause damage in a passive soak can cause visible deterioration within minutes inside an ultrasonic tank.

Surface Etching and Micro-Pitting

Even when corrosion is not obvious, micro-pitting can occur beneath the surface. This is particularly problematic for:

- Jewelry

- Watch components

- Precision-machined metal parts

- Firearms

- Dental or surgical tools

Once micro-pitting forms, the surface becomes more prone to future corrosion and may lose reflectivity or structural integrity. This damage cannot be reversed and often requires refinishing or replacement.

Discoloration and Staining

The wrong solution can cause staining or discoloration, such as:

- Brass turning pink or dark brown

- Copper developing black spots

- Stainless steel showing rainbow streaks

- Acrylic retainers turning cloudy

- Jewelry stones losing clarity

These color changes are often signs of chemical incompatibility rather than dirt. Ultrasonic agitation intensifies the reaction, producing uneven or rapid discoloration.

Residue Build-Up and Re-Deposition

Without the right emulsifiers and suspension agents, contaminants lifted by cavitation can redeposit onto surfaces. This results in:

- Cloudy films

- Greasy residues

- Streaking on glass

- Smudges on precision parts

- White spots from minerals

This happens frequently when users attempt to clean with plain dish soap or heavily diluted solutions lacking proper soil suspension chemistry.

Damage to the Ultrasonic Machine

Using the wrong chemistry can harm the machine itself. Common issues include:

- Corrosion of the stainless steel tank due to strong acids or chlorides

- Foaming overflow damaging electronics

- Solvent vapors harming seals or plastic housings

- Build-up of residues decreasing transducer efficiency

Over time, these issues reduce cleaning power and may void warranties.

Safety Hazards

Industrial-strength ultrasonic solutions can be hazardous if used incorrectly in home environments. Strong solvents or acids produce fumes, require ventilation, or demand protective gear. When paired with heated ultrasonic cleaners, the risks increase due to vaporization.

In short, the wrong ultrasonic cleaning solution does not simply underperform; it can damage both the item and the equipment. To avoid these pitfalls, understanding how to choose the correct solution is essential.

How to Choose the Right Ultrasonic Cleaning Solution

Selecting the appropriate ultrasonic cleaning solution is not about picking the strongest formula or the one with the most ingredients. Instead, it’s about finding a formula that matches both the material you’re cleaning and the type of contamination you’re removing. A perfectly balanced solution will deliver excellent cleaning performance while preserving surface integrity, extending equipment life, and preventing accidental damage. Choosing the right solution requires understanding your item, your contaminants, and the chemistry that works best for each situation.

Identify the Material You’re Cleaning

The first step is determining the material composition. Ultrasonic cleaning solutions are optimized for specific material families:

- Stainless steel tolerates most neutral and alkaline solutions.

- Aluminum requires mild alkaline or neutral formulas to prevent etching.

- Brass and copper need inhibitors to prevent darkening or pinking.

- Plastics and acrylics require gentle, neutral solutions with no solvents.

- Jewelry demands a neutral, low-foam formula, especially for soft stones.

- Electronics need solutions specifically designed for aqueous circuit cleaning.

- Carburetors and engine parts require powerful alkaline degreasers.

- Dental tools and retainers benefit from neutral enzymatic cleaners.

Understanding the material ensures chemical compatibility and eliminates formulas that might corrode or discolor sensitive surfaces.

Determine the Type of Contamination

Different soils require different chemistry. Identify the primary kind of residue:

- Oil, grease, or hydrocarbons → alkaline or solvent-assisted formulas

- Protein, blood, saliva, biological debris → enzymatic cleaners

- Mineral deposits or scale → acidic descalers

- Carbon buildup or burnt residues → strong alkaline degreasers

- Light dirt or dust → neutral, gentle solutions

- Oxidation or tarnish → specialized metal-safe acidic or reducing agents

This step ensures that the solution’s active ingredients target your specific contaminants effectively.

Match the pH to the Material and Soil

pH determines cleaning aggressiveness:

- Neutral (pH 6–8) → jewelry, plastics, optics, dental appliances, electronics

- Mild alkaline (pH 8–10) → general metal cleaning, light oils, shop dust

- Strong alkaline (pH 10–14) → engine parts, industrial grease, carbon

- Mild acidic (pH 4–6) → rust and mineral removal, brass brightening

- Strong acidic (below pH 4) → industrial descaling only

Selecting the correct pH prevents corrosion, discoloration, or material deterioration.

Consider Whether Enzymes Are Needed

If you are cleaning anything that has been in contact with biological matter, enzymatic solutions offer unmatched performance. They break down proteins, fats, and starches safely without harsh chemicals. This makes them ideal for:

- Medical instruments

- Dental tools

- Retainers and aligners

- Food-processing equipment

If your contamination is primarily biological, enzymes are essential.

Evaluate the Need for Solvents

Solvents deliver extra power for oily or hydrocarbon-heavy soils. However:

- Avoid solvents for plastics, adhesives, or coated surfaces.

- Use solvent-enhanced formulas for automotive, aerospace, or industrial parts.

- Choose aqueous, low-residue solvents for electronics.

Solvent choice must be precise to prevent surface damage.

Check for Corrosion Inhibitors

Any ultrasonic cleaning involving metal parts benefits from corrosion inhibitors. If the solution does not contain inhibitors, metal may discolor or corrode quickly. This is especially crucial for:

- Brass, copper, and aluminum

- Precision machined parts

- Tools with sharp edges

- Firearms and metal mechanisms

- Watchmaking and horology components

Look for solutions that specify “metal-safe” or “contains corrosion inhibitors.”

Assess Foaming Behavior

Foam interferes with ultrasonic cavitation. Solutions meant for ultrasonic cleaning must be low-foam or foam-controlled. Avoid any formula that produces thick suds, such as:

- Dish soap

- Laundry detergent

- Household cleaners

Low-foam performance ensures strong cavitation and even cleaning.

Review Manufacturer Recommendations

Manufacturers of ultrasonic cleaners often specify compatible solution types. Some units cannot handle solvents or require water-only formulas. Additionally, some items—especially jewelry or electronics—have specific cleaning guidelines. Whenever possible, follow manufacturer recommendations for both the item and the machine.

Balance Safety, Strength, and Frequency

Aggressive solutions might clean faster but can also wear down materials if used frequently. Neutral cleaners may require longer cycles but offer superior material safety. Balance cleaning power with long-term preservation. If you clean valuable or delicate items regularly, a gentler formula might extend their lifespan even if it takes an extra few minutes.

Start with the Mildest Effective Option

When in doubt, always begin with a gentle formula and increase strength only when necessary. Ultrasonic energy multiplies the cleaning power of chemicals, so mild solutions often perform much better than expected. Stronger chemicals should be reserved for heavy industrial maintenance or hardened contamination.

Choosing the right solution transforms ultrasonic cleaning from a simple process into a finely tuned combination of physics and chemistry. With the right formula, even the most delicate items can be cleaned safely and thoroughly. With the wrong one, damage can be swift.

Final Thoughts: Why Understanding the Ingredients Helps You Clean Better

Ultrasonic cleaning may look effortless from the outside, but every effective cleaning cycle depends on the chemistry suspended in the tank. The ingredients inside an ultrasonic cleaning solution determine how efficiently cavitation bubbles form, how quickly contaminants dissolve, and how safely the treated material is preserved. When you understand what these solutions are made of, you gain the ability to choose the formula that truly fits your cleaning task, rather than relying on guesswork or trial and error.

Knowing the difference between surfactants, chelating agents, enzymes, solvents, corrosion inhibitors, and stabilizers helps you understand why each solution behaves differently in the tank. These ingredients are not interchangeable; each plays a precise role in shaping how the fluid interacts with contaminants and with the ultrasonic waves themselves. A solution rich in surfactants may excel at breaking surface tension, but without proper chelators, even the best surfactant blend can struggle in hard water. Enzymes can break down biological residues flawlessly, yet offer little help against carbon deposits or engine grease. Strong alkalines may remove oils with ease, but without corrosion inhibitors, they can damage sensitive metals or delicate finishes.

Understanding the chemical structure of your cleaning solution also protects the items you clean. Every material has its own tolerances and vulnerabilities. Metals differ from plastics; coatings differ from bare surfaces; gemstones react differently depending on their mineral structure. The wrong solution can cause micro-pitting, clouding, discoloration, or structural deterioration, especially when ultrasonic cavitation amplifies the chemical reaction. Choosing the correct formula ensures that cleaning is both powerful and gentle, removing soil without damaging the item underneath.

Ultrasonic cleaning is more than a modern convenience; it is a precise balance of physics and chemistry. Cavitation provides the physical force, but chemistry provides direction and control. When both work together in harmony, cleaning becomes faster, deeper, and far more consistent than manual methods. Items emerge from the tank not just visibly cleaner but restored to a level of clarity and precision that would be difficult to achieve by hand.

Whether you are removing polishing compound from jewelry, degreasing engine parts, cleaning dental tools, restoring musical instruments, brightening laboratory glassware, or maintaining delicate electronics, the right ultrasonic cleaning solution ensures that cavitation performs at its highest potential. When you understand what these solutions are made of, you no longer view ultrasonic cleaning as a simple soak—you see it as a powerful science designed to protect, preserve, and perfect the surface of anything it touches.

With this knowledge, you’re equipped to choose wisely, clean effectively, and maintain your equipment and items with confidence. The solution you choose shapes the outcome you get, and understanding its composition empowers you to unlock the full potential of ultrasonic cleaning.

Granbo Ultrasonic

Granbo Ultrasonic